![After years of searching, Colin McNelley stands at the site of Willey Family grave in New Hampshire [photo by Robert Gillis]](http://www.robertxgillis.com/wp-content/uploads/File0268.jpg)

Published [full text] in the Boston City paper, 9/2015 and the Foxboro Reporter [Edited for print, full text on web site] 10/2015

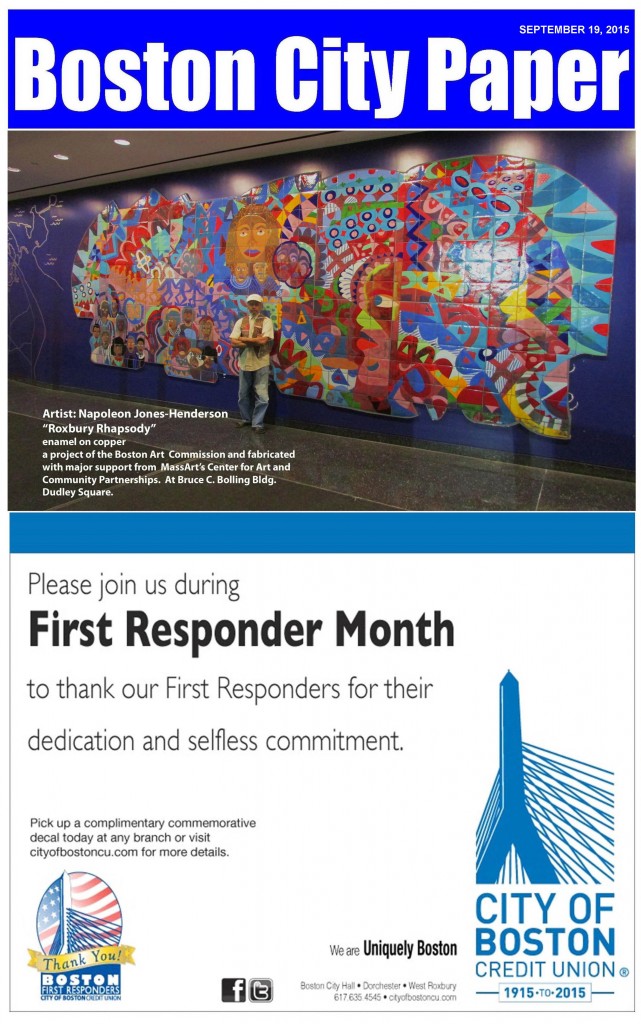

Recently, my nephew Colin made me very proud when he successfully completed his own historical quest. By using research and deductive reasoning, and by his own cleverness and persistence, he solved a mystery of sorts.

To clarify why this is important, I need to first explain that my family has been traveling to the White Mountains area of New Hampshire (specifically, North Conway / Bartlett / Glen) since I was a little boy. The area is very popular as a year-round destination for hiking, skiing, sight-seeing, shopping, and family fun. Decades ago, we fell in love with this breathtakingly scenic area of the country, which we call our mountain home. Over the years we continued to visit, hitting all the tourist attractions, rides, shops and also took in the spectacular natural beauty of the region on walks and hikes. To say we love the place is an understatement.

The tradition of visiting and enjoying the area continued; we travel here with Mom every year and as we got older my sister Theresa and I both brought friends, other family and our spouses here, and Theresa started bringing her children.

Colin loves the area; and by the time he was about eight, he developed a fascination with the Willey Family of Crawford Notch. He read about them, and he was intrigued by their lives — and their tragic fate.

Their story is arguably the most famous episode in the area’s history — It was nearly two hundred years ago, in 1826, during the same summer in which John Quincy Adams was President of the United States, this nation celebrated the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and mourned the deaths of presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams.

A year previously, Samuel Willey, Jr. of Bartlett has moved into a small house in Crawford Notch with his wife, five children, and also two hired men. Within a year, the house had been enlarged and improved upon, and the family operated it as an inn to accommodate travelers through the mountains.

About a year later, in June 1826, the family was horrified to witness a great mass of land fall from the mountainside and come crashing to the valley floor. It is believed because of this event, Mr. Willey created a cave-like shelter a short distance above the house — a safe place to which they could flee should another landslide threaten their home.

What happened next is tragic; the story unfolds on nhstateparks.org and countless texts and is best described in those words:

“During the night of August 28, 1826, after a long drought which had dried the mountain soil to an unusual depth, came one of the most violent and destructive rain storms ever known in the White Mountains. The Saco River rose 20 feet overnight. Livestock was carried off, farms set afloat, and great gorges were cut in the mountains. Two days after the storm, anxious friends and relatives penetrated the debris-strewn valley to learn the fate of the Willey family. They found the house unharmed, but the surrounding fields were covered with debris. Huge boulders, trees, and masses of soil had been swept from Mt. Willey’s newly bared slopes. The house had escaped damage because it was apparently situated just below a ledge that divided the major slide into two streams. … Mr. and Mrs. Willey, two children, and both hired men were found nearby, crushed in the wreckage of the slide. The bodies were buried near the house and later moved to Conway. Three children were never found. The true story of the tragedy will never be known.”

Since no one who was there survived, we don’t know if perhaps the Willeys fled from the house to try to get to their cave shelter, only to be killed in the landslide, or perhaps they were attempting to climb the mountain to outrace the rising floods. Whatever really happened, we will never know.

It’s a heartbreaking tale, made more tragic by the irony that their house survived intact while the family was killed — the boulders above the house apparently prevented the landslide from engulfing the home. Ironically, if the family had stayed put in the house, they would likely have survived.

It’s so very sad, especially when one considers how difficult their life must have been — these poor souls had such a hard life; “Hardscrabble” probably doesn’t begin to describe the way they worked and lived. There was no such thing as a modern convenience. Everything was done by hand. These good people WORKED and forged their lives out of the mountains.

And so, the story was told and retold and became a legend. Everyone who visits this area has heard of the Willeys and their tragic fate.

Today, nearly two centuries after the catastrophe, Crawford Notch State park is a 6,000 acre popular tourist spot that still features spectacular natural beauty, hiking trails, camping, waterfalls, fishing, wildlife viewing, walking paths, and a pretty lake where ducks play. There’s even a small gift shop with snacks, typical New Hampshire souvenirs and postcards, and awesome fudge candy.

At the base of what is now called Mount Wiley, a large stone marks the site of the Willey house, and a little up the incline are the boulders that are reputed to have saved the house itself from destruction.

We go every year. And so does Colin.

Now, as he grew older, Colin, along with the family, enjoyed the North Conway/Bartlett vacations and all the natural and family attractions, and invariably, every single vacation, the subject of the Willeys came up. And as he got older he wondered more and more, where were they buried?

Now, to be very clear, these were just family vacations and not historical investigation trips, and the “research” such as it was, hardly comprehensive — we don’t want to give anyone the impression that we spent our yearly precious annual getaway interviewing locals and combing vast archives searching for the Willey family — it was more of a passing question, a wondering, but at least some time each year was devoted to the subject, usually by Colin. FAR more time was devoted to shopping at Zebs, riding the Conway Scenic Railroad, sliding down Attitash Mountain, taking countless photographs of the spectacular natural vistas, eating sugary food, and reminiscing about past vacations here while creating new memories.

We’re so happy when we visit Bartlett / North Conway.

But the Willey question kept festering in Colin’s mind, and each year, he would bring them up, and at each visit to Crawford Notch, he would spend a little time in one of the buildings at Crawford Notch that serves as a small museum of sorts to the history of the area. The museum even includes a tabletop re-creation of that landslide and other information about the Willey family — but not clues to the final resting place of the Willeys.

In fact, NOWHERE will you find directions to where the family is buried. There’s no plaque at Crawford Notch directing you to the gravesite, and what we found in books and even the web seems contradictory — one text said the family was buried in Conway, another North Conway, another Intervale, and so on.

I got the feeling that perhaps authors were being deliberately vague, and caretakers of Crawford Notch didn’t seem to know either.

To his credit, Colin DID locate the grave of one of the handymen killed in the landslide — a Mr. David Allen, who was buried in Bartlett cemetery. And being Colin, he looked in the entire small cemetery and found the small stone marker — and then asked to come back so he could put some flowers on the grave, because Colin is awesome.

So the years went by — and it became part of the vacations that Colin and the family started asking around whenever they visited. A letter to the Conway Sun newspaper yielded no response, but they kept looking, and they would ask when they found someone who might know. Still, no answers. And each year, we continued to have our vacation fun and put the Willey questions aside as we turned toward more family and touristy type fun.

But one year was different. Theresa explains, “One year, it was, “find the Willeys.” — We did all the regular things — Shopping in North Conway, Cathedral Ledge, Conway Railroad, Zeb’s, but we REALLY looked around [for the Willeys].”

But still, they had no luck.

So, back to August of 2015, coincidentally during the same week as the 189th anniversary of the landslide. We’re back in North Conway for a visit, and Colin was waiting in the car while Mom and I picked up some groceries at the supermarket. It was pouring rain, and when we got back and opened the car door, Colin looked up from his omnipresent cell phone and announced, “I found the Willeys.”

This was exciting and we asked him to explain.

He had his lead: he explained that the previous day, in conversation, we were ideally wondering if someone we knew in the past had died, and I mentioned that I doubted it because I could find no record of that person’s obituary on the web. Colin then realized: When someone dies in the United States, there is a record of that milestone.

There. HAS. To Be. A RECORD.

“We need to go to the library,” he said.

I should remind the reader that Colin is 19. A teen-ager saying, “We need to go to the library” REALLY impressed me, but then again, Colin is always impressing me.

So on that VERY rainy Tuesday, for the first time in four decades of traveling to this area I stepped into the cozy confines of the North Conway library. It’s a very small building near the Mount Washington Observatory Museum on Main Street, and very homey and well equipped, making great use of a small space. I really liked it.

Colin explained to the librarian what he was looking for, could she help?

Well, the three lovely ladies who run the library were delighted and eager to do so, and Colin and I climbed the spiral stairs to the second level where a very helpful librarian worked with Colin while I made friends with the library dog, Dusty.

In short order, Colin had the EXACT location of the Willey’s final resting place.

Colin thanked the librarians — and I VERY much echo that sentiment: They were beyond helpful and kind and they are the reason my nephew could complete this quest successfully. Thank you staff of the North Conway Public Library (and Dusty too!) for being so helpful!

So we all set back out into the rain, we drove to the place, directions in hand, and were still dubious, as we began walking.

But then Colin yelled, “I FOUND IT! I FOUND IT!” and started running.

Nestled in a tiny grove of trees:

The Willey cemetery.

Not exactly hidden, not exactly in plain sight.

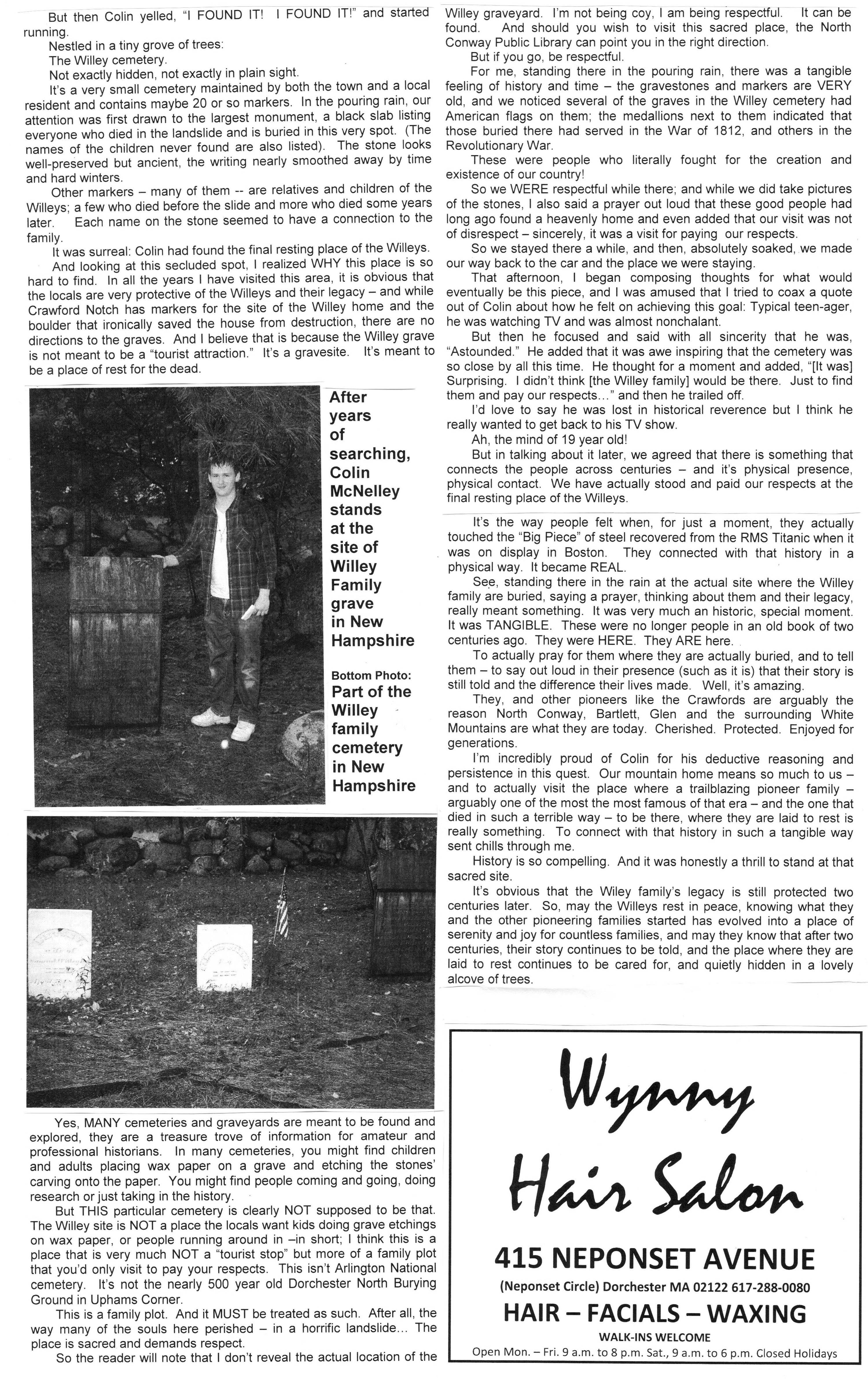

It’s a very small cemetery maintained by both the town and a local resident and contains maybe 20 or so markers. In the pouring rain, our attention was first drawn to the largest monument, a black slab listing everyone who died in the landslide and is buried in this very spot. (The names of the children never found are also listed). The stone looks well-preserved but ancient, the writing nearly smoothed away by time and hard winters.

Other markers — many of them — are relatives and children of the Willeys; a few who died before the slide and more who died some years later. Each name on the stone seemed to have a connection to the family.

![Part of the Willey family cemetery in New Hampshire [photo by Robert Gillis]](http://www.robertxgillis.com/wp-content/uploads/File0299.jpg)

And looking at this secluded spot, I realized WHY this place is so hard to find. In all the years I have visited this area, it is obvious that the locals are very protective of the Willeys and their legacy — and while Crawford Notch has markers for the site of the Willey home and the boulder that ironically saved the house from destruction, there are no directions to the graves. And I believe that is because the Willey grave is not meant to be a “tourist attraction.” It’s a gravesite. It’s meant to be a place of rest for the dead.

Yes, MANY cemeteries and graveyards are meant to be found and explored, they are a treasure trove of information for amateur and professional historians. In many cemeteries, you might find children and adults placing wax paper on a grave and etching the stones’ carving onto the paper. You might find people coming and going, doing research or just taking in the history.

But THIS particular cemetery is clearly NOT supposed to be that. The Willey site is NOT a place the locals want kids doing grave etchings on wax paper, or people running around in — in short; I think this is a place that is very much NOT a “tourist stop” but more of a family plot that you’d only visit to pay your respects. This isn’t Arlington National cemetery. It’s not the nearly 500 year old Dorchester North Burying Ground in Uphams Corner.

This is a family plot. And it MUST be treated as such. After all, the way many of the souls here perished — in a horrific landslide… The place is sacred and demands respect.

So the reader will note that I don’t reveal the actual location of the Willey graveyard. I’m not being coy, I am being respectful. It can be found. And should you wish to visit this sacred place, the North Conway Public Library can point you in the right direction.

But if you go, be respectful.

For me, standing there in the pouring rain, there was a tangible feeling of history and time — the gravestones and markers are VERY old, and we noticed several of the graves in the Willey cemetery had American flags on them; the medallions next to them indicated that those buried there had served in the War of 1812, and others in the Revolutionary War.

These were people who literally fought for the creation and existence of our country!

So we WERE respectful while there; and while we did take pictures of the stones, I also said a prayer out loud that these good people had long ago found a heavenly home and even added that our visit was not of disrespect — sincerely, it was a visit for paying our respects.

So we stayed there a while, and then, absolutely soaked, we made our way back to the car and the place we were staying.

That afternoon, I began composing thoughts for what would eventually be this piece, and I was amused that I tried to coax a quote out of Colin about how he felt on achieving this goal: Typical teen-ager, he was watching TV and was almost nonchalant.

But then he focused and said with all sincerity that he was, “Astounded.” He added that it was awe inspiring that the cemetery was so close by all this time. He thought for a moment and added, “[It was] Surprising. I didn’t think [the Willey family] would be there. Just to find them and pay our respects…” and then he trailed off.

I’d love to say he was lost in historical reverence but I think he really wanted to get back to his TV show.

Ah, the mind of 19 year old!

But in talking about it later, we agreed that there is something that connects the people across centuries — and it’s physical presence, physical contact. We have actually stood and paid our respects at the final resting place of the Willeys.

It’s the way people felt when, for just a moment, they actually touched the “Big Piece” of steel recovered from the RMS Titanic when it was on display in Boston. They connected with that history in a physical way. It became REAL.

See, standing there in the rain at the actual site where the Willey family are buried, saying a prayer, thinking about them and their legacy, really meant something. It was very much an historic, special moment. It was TANGIBLE. These were no longer people in an old book of two centuries ago. They were HERE. They ARE here.

To actually pray for them where they are actually buried, and to tell them — to say out loud in their presence (such as it is) that their story is still told and the difference their lives made. Well, it’s amazing.

They, and other pioneers like the Crawfords are arguably the reason North Conway, Bartlett, Glen and the surrounding White Mountains are what they are today. Cherished. Protected. Enjoyed for generations.

I’m incredibly proud of Colin for his deductive reasoning and persistence in this quest. Our mountain home means so much to us — and to actually visit the place where a trailblazing pioneer family — arguably one of the most the most famous of that era — and the one that died in such a terrible way — to be there, where they are laid to rest is really something. To connect with that history in such a tangible way sent chills through me.

History is so compelling. And it was honestly a thrill to stand at that sacred site.

It’s obvious that the Wiley family’s legacy is still protected two centuries later. So, may the Willeys rest in peace, knowing what they and the other pioneering families started has evolved into a place of serenity and joy for countless families, and may they know that after two centuries, their story continues to be told, and the place where they are laid to rest continues to be cared for, and quietly hidden in a lovely alcove of trees.

You know, I’ve been visiting our mountain home since I was a child, and it continues to teach me things: How to relax, to have an appreciation of God’s creation and natural beauty, and constantly reminds me of the wonderful connection to my own past of family adventures there. And some years, it just reminds me that’s it’s good to get away with the family for a few days in our mountain home.

And in 2015, at my mountain home, an awesome 19 year young man, like a son to me in every way that matters, taught us this: never give up on history: It’s waiting to be found, and to continue its teachings.

Revised version for the Foxboro Reporter

Due to space limitations, the Foxboro Reporter needed to run an edited version of this piece so I pared it down to the following. As always I remain grateful to Bill Stedman and the staff of the Reporter; they could have just said, “Can’t run it, too long for content,” but gave me the opportunity to edit it down, and even ran the full version on the Reporter web site. Here is the edited version: